Summary

Electronic components were once assumed to remain available for years, failing only through physical wear or damage. This assumption no longer holds true.

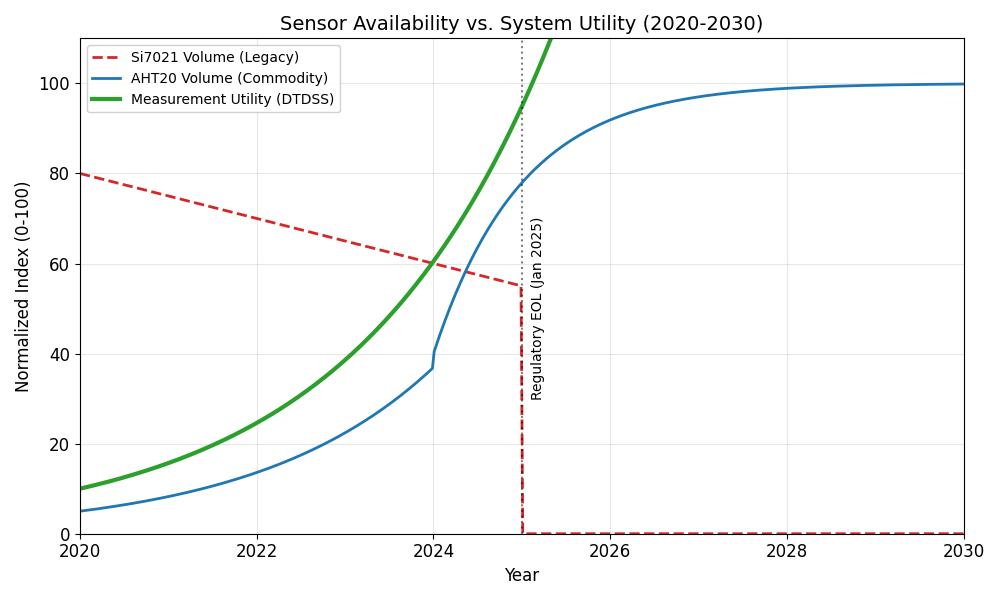

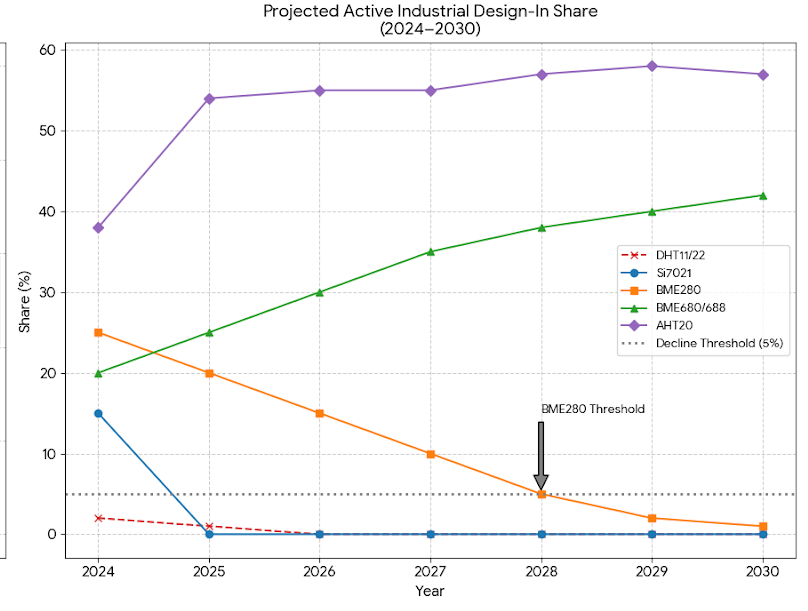

This article introduces a model called The Common Curve of Sensors. The model describes how the useful life of a sensor is increasingly splitting into two distinct trajectories.

The first trajectory involves hardware, which is becoming increasingly fragile. Sensors can disappear from the market overnight due to regulatory changes or manufacturing constraints.

The second trajectory involves software, which is steadily rising in importance. Intelligent algorithms can now transform inexpensive commodity sensors into instruments that perform comparably to specialized scientific equipment.

We examine the discontinuation of the widely used Silicon Labs Si7021 sensor as an example of why depending solely on hardware is problematic. We then demonstrate how our software framework, DTDSS, enables a seamless transition to less expensive sensors like the Aosong AHT20 without sacrificing measurement quality.

1. Hardware Fragility and Regulatory Discontinuation

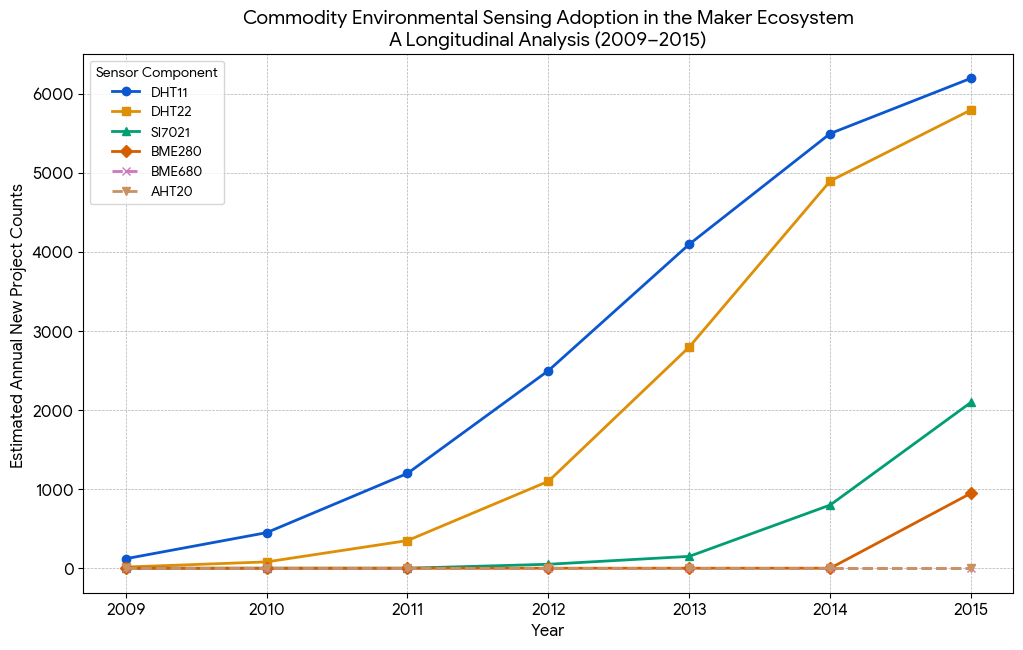

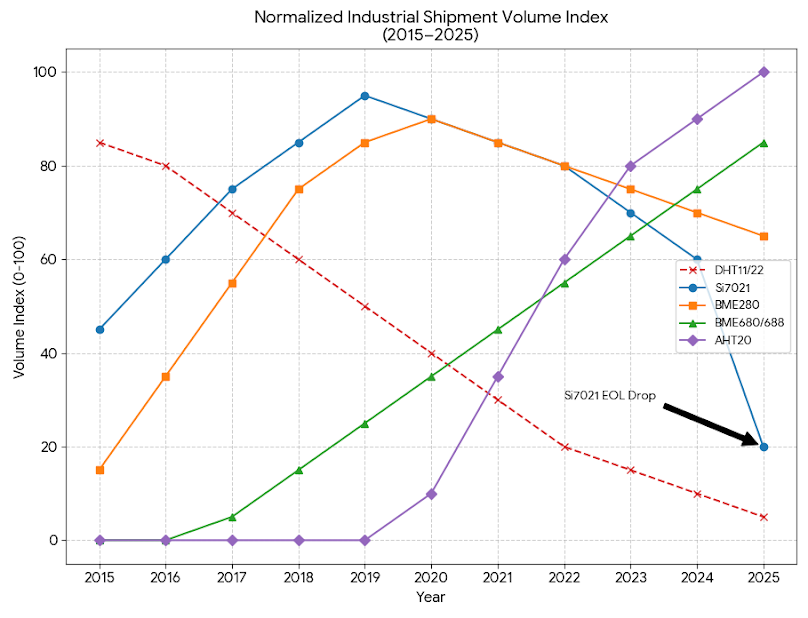

Traditional models assumed that electronic components would be discontinued only when superior alternatives emerged. Today, however, a component can be removed from production immediately due to environmental regulations. This phenomenon represents a fundamental shift in how we must approach sensor selection.

1.1 The Si7021 Discontinuation

For over a decade, the Silicon Labs Si7021 served as an industry standard for temperature and humidity measurement. On January 29, 2025, Silicon Labs issued an End of Life notice that effectively terminated the entire product line.

The sensor was neither defective nor technically obsolete. The problem lay within its material composition. Specifically, the sensor relied on an insulator called Polybenzoxazole, commonly abbreviated as PBO.

Compliance audits subsequently revealed that this PBO material contained per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS or forever chemicals. Due to strict regulations from both the European Union and the US Environmental Protection Agency, Silicon Labs was required to halt production immediately.

The practical consequence was significant. There was no direct replacement available. Engineers who had designed systems around this sensor found themselves without options, and the hardware availability for this sensor dropped to zero essentially overnight.

2. Market Response and Commodity Substitution

When a sudden discontinuation occurs, engineers must quickly identify replacement components. Since no high-end alternative was readily available, the market naturally shifted toward what was accessible and affordable.

This transition caused a substantial increase in adoption for the Aosong AHT20. This sensor is mass-produced, widely available, and costs significantly less than its predecessors, often measured in cents rather than dollars.

The AHT20 uses standard, compliant materials and integrates easily into modern circuit boards. While it is nominally a less expensive device, switching to a lower-cost sensor does not necessarily mean accepting lower quality data. With appropriate software, the performance gap can be effectively closed.

3. Software-Driven Value Enhancement

This section presents the central argument of our hypothesis. Even when hardware becomes simpler or less expensive, such as transitioning from the Si7021 to the AHT20, the practical value derived from the sensor can actually increase through intelligent algorithmic processing.

We call our software solution Differential Temporal Derivative Soft-Sensing, abbreviated as DTDSS. This framework essentially functions as a computational layer that significantly enhances the capabilities of basic sensor hardware.

3.1 How DTDSS Operates

Rather than simply querying a sensor for the current temperature reading, DTDSS analyzes how temperature changes over time and compares measurements between two sensors simultaneously.

The configuration uses two sensors in a differential arrangement. The first sensor, called the Reference Node, is positioned in shade and measures ambient air conditions. The second sensor, called the Flux Node, is placed under a clear dome where it is exposed to direct sunlight.

By measuring the temperature difference between the sun-exposed sensor and the shaded sensor, we can calculate the amount of radiant energy striking the surface. This approach allows us to measure solar radiation and heat flux without requiring expensive specialized instruments like pyranometers, which typically cost several hundred dollars.

3.2 Noise Reduction Through Inertial Filtering

Inexpensive sensors often produce noisy readings, where measurements fluctuate slightly even under stable conditions. To address this, we employ a filter called Inertial Noise Reduction, abbreviated as INR.

The filter operates similarly to image stabilization in cameras, which smooths out unintentional movement. INR applies this concept to temperature readings. It uses an adaptive mathematical approach based on exponential moving averages that can distinguish between genuine temperature changes and random noise.

The result is a mathematically reconstructed signal that is considerably smoother, allowing an inexpensive sensor to track rapid environmental changes, such as a cloud passing over the sun, with accuracy comparable to more expensive equipment.

3.3 Altitude Independence

Most sensors produce inconsistent readings at different elevations because air density varies with altitude. DTDSS addresses this by calculating air density in real time using the sensor's pressure readings.

The calculation relies on established thermodynamic relationships, specifically the Magnus-Tetens formula, to determine air density precisely at any given moment.

This means the system operates consistently whether at sea level or at high elevation, without requiring GPS positioning or manual calibration adjustments.

4. Conclusion

The Common Curve of Sensors demonstrates that we can no longer assume hardware will remain consistently available. Regulations change and materials become restricted, as the Si7021 discontinuation clearly illustrates. The hardware layer has become inherently fragile.

The software layer, however, proves considerably more resilient. By applying physics-based algorithms like DTDSS, we can take whatever compliant hardware is currently available, such as the AHT20, and transform it into a capable precision instrument.

Ultimately, the future of environmental sensing depends less on advancing silicon technology and more on developing sophisticated mathematical approaches.